Blurring the Line (Part 2) – Online/Offline

In the first part of this article series, I described one part of my explanation of what enabled the Internet to gain such an incredible penetration rate and a foothold in Korea – the infrastructure.

Here’s a fun way I like to look at the whole thing – if we look at the penetration of online video games into Korean culture as an explosion, the Internet infrastructure was the bomb used to set it off – but something needed to light its fuse, and set off the big bang. The fun part is when you realize that the big bang was caused by a lot of small bangs – PC bangs.

Yes, that does sound weird, and no, I’m not on any medication. Bang stands for a room in Korean, and if you followed so far, you’ll understand I’m talking about the Korean version of an internet cafe. For most of us, Internet cafe’s are a thing of the past. There’s wi-fi everywhere, and a huge part of the population has a smartphone with a data plan for when there is no wi-fi available, but that wasn’t the case in the early 2000’s.

The Rise of PC Bangs

Back in the day, a major part of the population didn’t even own a PC at home, but that didn’t stop Korean teenagers (and probably a significant portion of the adult populace) from wanting to play video games they saw other people playing on national television.

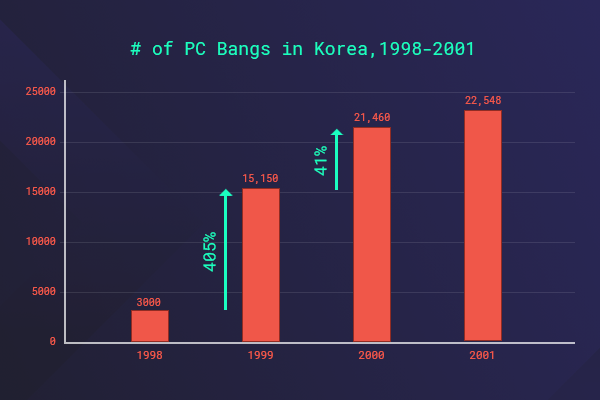

That demand, combined with a few other significant catalysts like the 1997 Asian economic crisis, which left a lot of rather tech-savvy Koreans looking for a way to make a living, and the aid of the government with its “10 Million People Internet Education” initiative and subsidies it provided allowed for monstrous growth in the number of PC bangs in Korea:

(Source: Korean Information Society)

With 20,000 new PC Bangs to spend their time and money in, Korean teenagers boosted the economy and created an entire ecosystem around online games that affected the offline world in Korea substantially – and that was way before anyone dreamt about selling a single in-app purchase in a mobile game, or what in-app purchases are!

This can help explain how Korea became such a huge market for mobile apps in general and games specifically – Koreans were used to paying an hourly fee to play video games in PC bangs back in 1999, as well as paying for in-game currency and items for MMORPG games since the early 2000’s, so it’s no surprise to see them spending upwards of 1.5 billion dollars on mobile games in 2017 (Source: Statista).

Naver’s Refusal to Fall in Line

While all of this was going on, Naver was being established. For those of you unfamiliar with Naver, the simplest way to describe it is would be “Korea’s Google”. Naver generated 3.5 billion dollars in revenue last year.

Fast forward around a decade into the future – it’s 2011, where mobile apps are huge and Naver is gigantic – and it’s Japanese subsidiary, NHN Japan takes a stab at instant messaging, with the LINE app.

It seems that Naver was timid about trying to combat the local KakaoTalk app, but they still wanted in on the instant messaging market, so tried their luck in a less saturated market for instant messaging apps – Japan. And man, that was a brilliant move.

Today, LINE has over 220 million MAU globally and generates over 270 million dollars per year, just from their sticker sales (Source: TechCrunch).

The next (and final) article in the series will discuss LINE’s ability to succeed offline and why we believe we’re going to see western companies attempt (and succeed) to imitate them in the coming years.