The Vicious Cycle of Click Spamming

In this article (click to jump to the section):

Fraud in the Mobile Adtech World

Fraudulent traffic has always been a major pain point of the adtech industry. Of course, it’s expected that using non-physical data products leaves ample room for manipulation. This is because it entails working at a high scale without the possibility of verifying every user’s existence.

The industry puts a lot of effort into combating fraud, but fraud methods evolve simultaneously and become more intricate to overcome newly developed fraud prevention solutions.

The adtech industry’s losses due to fraudulent traffic are estimated to reach $100 billion in 2023, according to Juniper Research—and that number is rising. Industry experts estimate that fraudulent installs account for 31% of iOS and 25% of Android app installs.

The major types of ad fraud in the mobile industry are:

- Click spam or click flooding (fraudsters using MMP links open multiple app store pages on users’ devices without the users being aware, and if a user happens to (organically) install one of the apps, the install is attributed to the fraudster);

- Click hijacking (a more sophisticated type of fraud where fraudsters predict the anticipated install brought by another provider and hijack the click just before the install happens);

- SDK spoofing (fraudsters create an imitation of a legitimate app install emulating real user activity and utilizing a real mobile device, whereas the install never took place).

As a veteran adtech product company with over 10 years of experience, our goal is to provide value and become a partner to our clients rather than being just another service provider. That’s why we listen to our customers and proactively address their concerns.

Multiple clients in the APAC region have raised concerns about how much trust to put in the UA costs they have seen from some partners. And while the numbers were strong and keeping the companies’ stakeholders happy, we sensed that something was off as they seemed far from being realistic.

The investigation run by our product and analytics team revealed an unprecedented amount of click spam by several of the key user acquisition partners.

While the amount of click spam has decreased in Western countries1, its presence remains strong in some regions, including APAC. The problem is still seen in emerging markets, and the industry should prioritize addressing the issue as it affects multiple stakeholders.

What is Click Spam?

Click spamming, sometimes referred to as click flooding, is a fraudulent traffic activity that abuses the loophole of the “last touch” attribution model. Fraudsters open multiple app store2 pages on real users’ devices without them knowing (or seeing the ad or the store page) and attribute an install that might theoretically happen organically in the next seven days. During this attribution window, as long as the “click” from the fraudster’s source was the last one, MMPs will assign the install to the fraudster.

In other words, if a user whose device was abused downloads the app organically while the attribution window is still open, the install is attributed to the fraudster.

How Does Click Spam Work?

There are a few relatively simple steps that fraudsters follow to run click spamming at scale:

- Using one of many self-serve (or sometimes a proprietary) DSP (demand-side platforms) that are particularly prone to abuse due to insufficient moderation, the fraudsters purchase the cheapest inventory available.

- The uploaded creative assets contain malicious code that prompts the device to open multiple app store pages (sometimes 20-30 at once) in the background without the user even realizing it. This process is called ad stacking.

- All the clicks from real users’ devices are now attributed to the fraudsters for the next seven days.

- If a user organically installs the app within the attribution window, the install will be attributed to the fraudster.

Click spamming works on assumption, and it targets apps that are likely to be installed organically by large groups of users. These are typically apps that rank high on charts, are top grossing, offer new services, are popular among new device owners, and more.

The Scale of Click Spamming

As click spamming tends to bring the CPI (cost per install) significantly lower than legitimate paid sources and sometimes produces higher engagement rates (by simply cannibalizing the organic traffic where users have high intent of using the app), companies providing this type of fraudulent traffic have higher chances of becoming the main user acquisition partner.

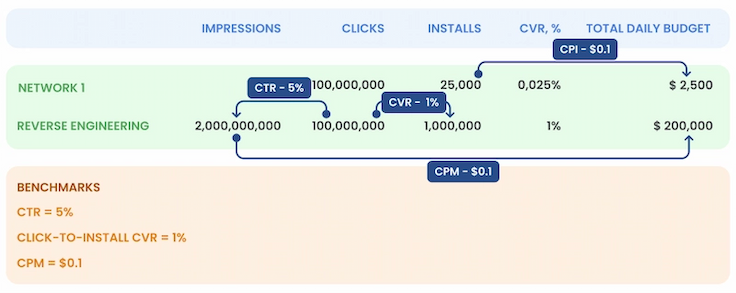

Let’s look at the real case of a Delivery vertical in India that our team examined. A fraudulent partner was bringing 25,000 installs per day and reporting 100,000,000 (100M) clicks per day, purposefully hiding the impressions (which otherwise would have been hardcoded). This didn’t draw the UA manager’s attention because the fraudster was a reputable company included as a top-performing company in one of the MMP’s reports.

Our first examination revealed an abnormal Click-to-Install CVR (conversion rate) of 0.025% (with an industry benchmark of around 1-2% depending on the app type and app vertical). The abnormal CVR raised a red flag and drove us to investigate further.

What we found is that trying to reverse engineer these numbers makes the performance anecdotal:

- In order to generate 100,000,000 (100M) clicks, even with a very generous CTR (click-through rate) of 5% (for a full-screen video), a total of 2,000,000,000 (2B) impressions should be served daily.

- Generating this number of impressions, even at a very low CPM (cost per mille) of $0.1, would cost an advertiser $200,000 daily.

- Finally, with the normal anticipated conversion rate of 1%, the number of installs generated by the source should lean towards 1,000,000 daily.

An important aspect of the programmatic mobile adtech industry is that all the Tier 1 SSPs (supply-side platforms) that provide high-quality traffic work on the CPM model exclusively.

Having a CPI (cost-per-install) or CPA (cost-per-action) agreement between a service provider and an advertiser is not unheard of (this actually happens quite a lot). Advertisers, thinking that they’ll only pay for installs or actions, feel that their budget is secured for growth.

In the case mentioned above, at a CPI of $0.1 per install with 25,000 installs daily, the daily campaign budget is $2,500 while the real daily budget of a campaign of this scale should have been $200,000.

What feels like huge savings is actually a budget loss.

The example above reflects the actual scale of the click spamming for a single mobile app on one of the biggest markets. Of course, not all the fraudulent traffic companies leave such apparent traces—in some cases, the scale can be more modest3. However, the number of clicks opening multiple attribution opportunities and Click-to-Install CVR should always attract the attention of a UA manager.

Vicious Cycle?

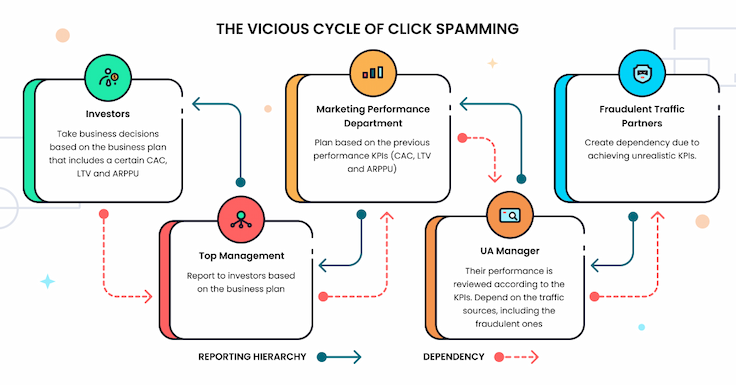

The problem of click spamming of this scale is much larger than that of the leaking budget alone. When the yearly marketing performance budget (along with the business plan and investor report) is built based on the results of the seemingly “best UA source,” this creates the vicious cycle of dependency on that traffic source.

Let’s see how click spamming affects multiple stakeholders.

- When the opportunity presents itself, a fraudulent UA partner starts providing the traffic and installs at a lower price than other partners while keeping up with (or even outperforming) other partners’ engagement KPIs. At a small scale, the reduction in organic traffic can be easily overlooked.

- The UA manager reports results to the performance department manager. In many cases, the UA department is separated from the ASO/organic traffic department which would see the decline in organic traffic (and would definitely get atypical results of A/B tests). Since different marketing departments within the same company might not communicate directly on a regular basis, the drop in organic traffic might remain unseen by the performance department, making it hard to attribute the drop to the new paid traffic source.

- The performance department manager builds a yearly budget based on the figures delivered by the fraudulent UA source.

- The numbers, including the user acquisition cost, eventually get to the yearly business plan that top management presents to the investors.

- Once the business plan is approved, the investors base their expectations on the invalid figures.

As multiple other traffic sources are having a hard time competing with the fraudulent UA traffic source in terms of both UA cost and engagement, the dependency on the fraudster company is growing.

On the macro level, the success of click spammers (and the fact that both clients and MMPs allow it to happen) affects the entire mobile industry. The ball keeps rolling for the click spammers as they have a higher chance of getting featured on MMPs’ performance indexes due to the methodologies used (and flying under the fraud protection suites’ radar):

- Volume ranking – number of installs: opportunistic tactics used by click spammers depend on the install event probability, hence they need to drive high volumes of traffic in order to increase their chances for install.

- Retention/IAP ranking: since the installs brought by click spammers are purely organic, it’s no wonder these companies manage to keep up with the organic benchmarks.

The Negative Effects of Click Spamming

- CAC cost. Dependency on the numbers for the UA managers means that investment is based on the prognosis.

- Organic traffic. By design, click spamming attributes and cannibalizes organic traffic in favor of a fraudulent partner.

- MMP cost. Since the installs are attributed as paid, it adds the cost to the MMP.

- Unrealistic engagement expectations from other paid partners. There is a principal difference between organic and paid traffic. As for organic traffic, users typically have higher intent of downloading and using the app, which corresponds to the pull marketing strategy. Users acquired through paid sources have a lower intent of using the app without being pushed.

- App store ranking. Low conversion between app store page views and installs signals to app stores about low user interest in the promoted app, eventually lowering the app’s rank.

- Underappreciation of legitimate traffic sources. Tier 1 ad exchanges work exclusively on the CPM model due to maximum transparency. While CPI/CPA models seem to bring more “clear” and predictable outcomes, it makes it easier for fraudsters to engage in click spamming and other fraud at scale.

- Cost of mobile data for users. In countries where mobile data is limited and expensive, like India, the vast majority of users purchase limited data packages from mobile providers and use their internet wisely. When fraudsters open multiple app store pages in background processes, loading pages can take up a good chunk of users’ data packages.

Detecting and Preventing Click Spam

- Ask for a number of impressions. Click spammers typically don’t share the number of impressions. Instead, they share the number of clicks and installs—for a good reason. Because the impressions are not displayed to the real users, click spammers would need to hard-code those.4

- Check the conversion rates. The click-to-install conversion rate will show an imbalance and be far away from the industry benchmarks by vertical.

- Calculate the cost feasibility. Calculating how much it would cost a partner to acquire users and comparing those numbers to the amount charged might shed light on suspicious activity.

- Run a test. If you suspect a UA partner is already click spamming, the reliable way to check is to pause the partner (or multiple ones) for a period of 10 days (as the standard attribution window lasts seven days) and see whether there is growth in the organic installs.

- Monitor your traffic:

- Organic: A sudden decline in organic traffic might signal that it’s time to run an audit on your new partners.

- Assisted installs in paid traffic: While assisted installs and some overlapping in sources are perfectly expected, the disproportional presence of a partner in assisted installs should raise a flag and urge further investigation.

- Implement the right due diligence process. We recommend performing deep research on the company. This means checking the number of their employees, reviewing references from their clients, and going over their case studies to make sure you are working with a reputable partner.

Another important aspect of the due diligence process is asking the right questions: Discovering partners’ traffic sources and how they access this traffic might be the key. The “secret sauce” in adtech is always a technology behind, so secrecy in the aspects mentioned should raise suspicion.

Unfortunately, due diligence alone is not enough to prevent fraudsters from taking over the budget. As mentioned before, some fraudsters in our case study were included in the industry’s performance rating.

- Provide the right incentives to the UA team. Currently, UA managers’ performance is measured by ROAS. This perspective should be shifted towards bringing in fraud-free traffic.

- Don’t be ignorant. If something looks too good, there is a great chance it is.

Notes:

1 While the amount is lower in Western countries, it still exists due to the negligence and ignorance of buyers who let it happen. However, Western companies’ policies are normally stricter and include processes to ensure that due diligence is in place. Back ⤴️

2 We intentionally don’t specify the device type or the store, as click spamming equally affects Android and iOS apps. Back ⤴️

3 Modesty, however, is not a common trait of click spammers. Since fraudsters need to increase the probability of install, they must target more devices to open more attribution windows. Back ⤴️

4 One of the biggest MMPs—Adjust—tried to push the initiative not to attribute sources that don’t send impressions. Sadly, they later decided not to enforce it. Back ⤴️